Mastering Routes of Drug Administration: From Oral to Intranasal – A Clinician’s Guide

Explore the science and clinical nuances of every drug administration route. From oral tablets to intranasal sprays, learn how to optimize therapy, predict side effects, and ace exams in 2000+ words.

Every prescription is more than a chemical formula; it’s a delivery strategy that determines how effectively a drug reaches its target. In 2023, nearly one in ten adults in the United States required a medication that was not only potent but also delivered in the right form to improve adherence and outcomes. Imagine a 58‑year‑old man with uncontrolled hypertension who is non‑compliant because he dislikes swallowing large tablets. Switching him to a once‑daily oral solution or a transdermal patch can dramatically improve his blood pressure and quality of life. Understanding the science behind each route—how drugs are absorbed, distributed, metabolized, and eliminated—enables clinicians to tailor therapy to individual patients and to anticipate complications.

Introduction and Background

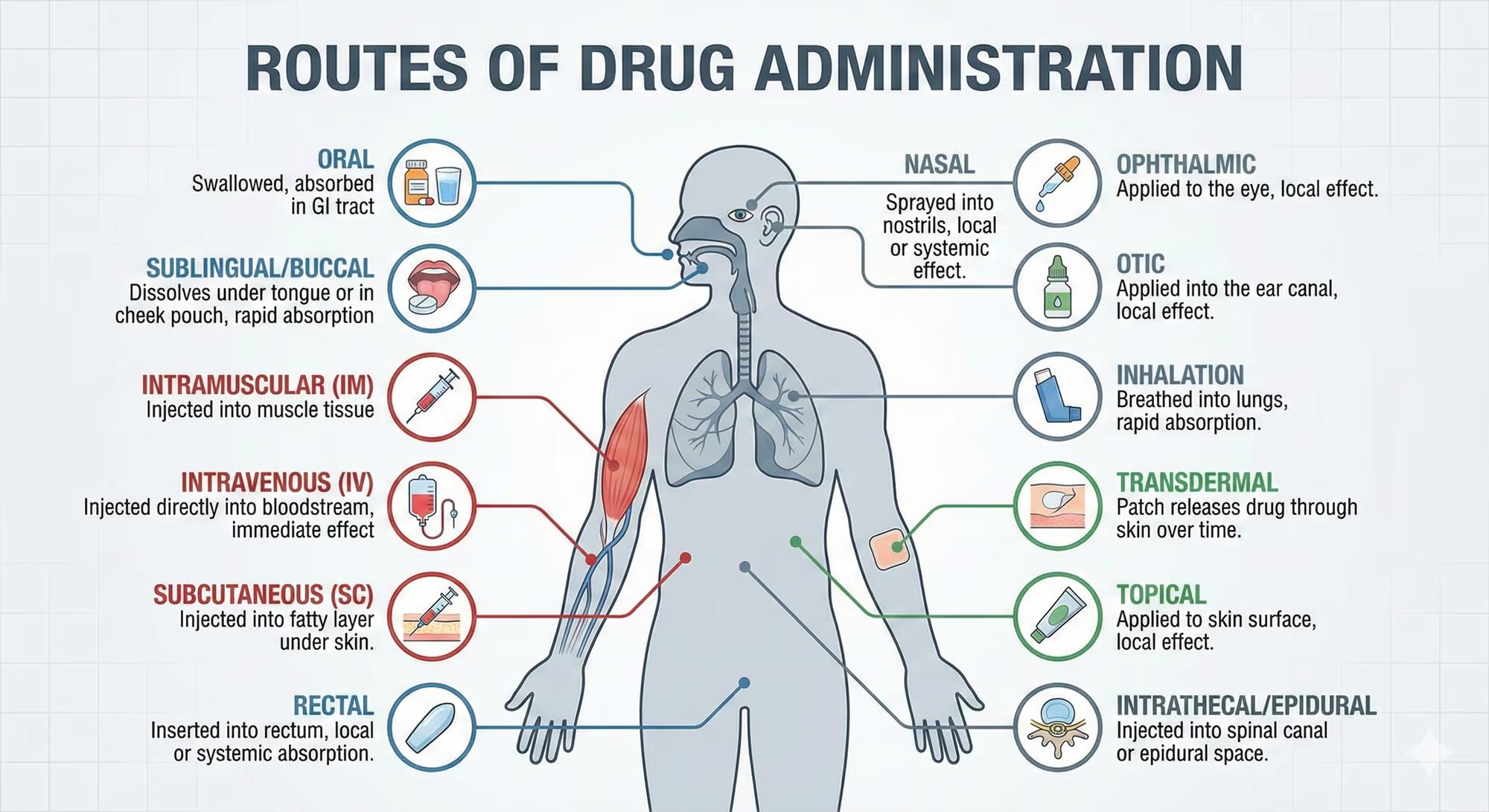

Routes of drug administration have evolved alongside pharmacology, reflecting advances in medicinal chemistry, patient preferences, and therapeutic needs. Historically, the oral route was the default due to convenience and low cost. However, the discovery of the first intramuscular injection in the 19th century and the advent of subcutaneous needles in the 20th century expanded options for rapid onset and improved bioavailability. Today, we also have inhalation devices, transdermal patches, rectal suppositories, and even intranasal sprays that bypass first‑pass metabolism.

Each route interfaces with distinct anatomical and physiological barriers—such as the gastrointestinal mucosa, skin, lung alveoli, or nasal cavity—affecting drug absorption kinetics and systemic exposure. Drug classes that benefit most from non‑oral routes include large‑molecule biologics, drugs with significant first‑pass metabolism, or medications requiring rapid onset of action (e.g., epinephrine for anaphylaxis). Understanding these interactions is essential for rational drug selection, especially in special populations such as pediatrics, geriatrics, or patients with hepatic or renal impairment.

Mechanism of Action

While the pharmacodynamic action of a drug—its binding to receptors or enzymes—remains constant regardless of the route, the route determines how quickly and how much of the drug reaches the systemic circulation to exert its effect. The following subsections illustrate key mechanisms for common drug classes across various routes.

Oral Administration

Oral drugs are absorbed primarily through the intestinal mucosa via passive diffusion, active transport, or carrier‑mediated processes. For lipophilic molecules, the intestinal brush border enhances permeability; for hydrophilic agents, transporters such as the sodium‑glucose cotransporter (SGLT1) can facilitate uptake. The absorbed drug then enters the portal circulation, exposing it to first‑pass hepatic metabolism before reaching systemic circulation.

Intravenous (IV) Administration

IV delivery bypasses all absorption barriers, placing the drug directly into the bloodstream. This route achieves 100% bioavailability instantly, making it ideal for emergencies, drugs with poor oral bioavailability, or when rapid therapeutic levels are required. The drug’s pharmacokinetics are governed solely by distribution, metabolism, and excretion, allowing precise control over plasma concentrations.

Intramuscular (IM) and Subcutaneous (SC) Administration

IM injections deposit drugs into muscle tissue, where rich vasculature facilitates absorption. SC injections place drugs into the adipose layer, which has slower blood flow, leading to a more prolonged absorption phase. Both routes rely on diffusion across the interstitial fluid and subsequent uptake by capillaries, with bioavailability ranging from 70% to 95% depending on the drug’s physicochemical properties.

Transdermal (TD) Administration

TD patches deliver drugs through the epidermis into systemic circulation via passive diffusion or iontophoresis. Skin penetration is limited by the stratum corneum; therefore, only small, lipophilic molecules (molecular weight <500 Da, logP 1–3) are suitable. The patch’s reservoir maintains a constant drug gradient, providing steady plasma levels over days.

Inhalation (Pulmonary) Administration

Inhaled drugs reach the alveoli, where the large surface area and thin epithelial barrier allow rapid absorption into the pulmonary capillary bed. This route achieves near‑instant systemic exposure with minimal first‑pass metabolism. It is especially useful for bronchodilators, corticosteroids, and vaccines requiring mucosal immunity.

Intranasal (IN) Administration

IN sprays exploit the highly vascularized nasal mucosa for rapid absorption. The nasal cavity’s mucociliary clearance can limit residence time; formulation strategies such as mucoadhesive polymers or viscosity enhancers prolong contact. IN delivery is advantageous for drugs needing quick onset (e.g., naloxone) or for vaccines targeting mucosal immunity.

Rectal and Vaginal Administration

Rectal suppositories and vaginal gels bypass the gastrointestinal tract, offering local and systemic effects. The rectal mucosa has a rich blood supply, allowing absorption into systemic circulation, while the vaginal route provides both local therapy (e.g., antifungals) and systemic bioavailability for certain hormones.

Clinical Pharmacology

Pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) profiles vary dramatically across routes. The following table summarizes key PK parameters for representative drugs delivered via oral, IV, and IM routes.

Drug | Route | Absorption (tmax) | Bioavailability (%) | Half‑life (h) | Metabolism (hepatic) | Elimination (renal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Amoxicillin | Oral | 1–1.5 | 90–100 | 1–1.5 | Minimal | Renal |

Amoxicillin | IV | Immediate | 100 | 1–1.5 | Minimal | Renal |

Insulin (Human) | SC | 30–90 | 90–95 | 4–6 | Minimal | Renal |

Insulin (Human) | IV | Immediate | 100 | 4–6 | Minimal | Renal |

Diazepam | Oral | 1–2 | 80–90 | 20–30 | Extensive hepatic metabolism | Renal |

Diazepam | IV | Immediate | 100 | 20–30 | Extensive hepatic metabolism | Renal |

Pharmacodynamics hinge on achieving therapeutic plasma concentrations. For instance, the therapeutic window of beta‑blockers is narrow; doses that exceed the upper limit can precipitate bradycardia and hypotension, while sub‑therapeutic levels fail to control cardiac arrhythmias. Monitoring parameters differ by route: IV infusions require frequent blood pressure checks, whereas transdermal patches necessitate skin assessment for irritation.

Therapeutic Applications

Oral: Antibiotics, antihyperglycemics, antihypertensives, antiepileptics, and most small‑molecule chemotherapies.

Intravenous: Sepsis management (e.g., ceftriaxone), anesthetic induction (propofol), emergency reversal of anticoagulation (vitamin K, PCC).

Intramuscular: Vaccinations (MMR, influenza), depot antipsychotics (haloperidol decanoate), and emergency epinephrine.

Subcutaneous: Insulin, heparin, certain biologics (adalimumab).

Transdermal: Nicotine replacement, fentanyl patches, hormone replacement (estradiol patches).

Inhalation: Asthma (albuterol), COPD (tiotropium), pulmonary hypertension (bosentan), and vaccines (influenza nasal spray).

Intranasal: Naloxone (opioid overdose), desmopressin (central diabetes insipidus), and vaccines (COVID‑19 nasal spray in trials).

Rectal: Loperamide for diarrhea, suppositories for hemorrhoids, and rectal diazepam for status epilepticus.

Vaginal: Local antifungals, hormonal contraception (vaginal ring), and local anesthetics.

Off‑label uses are common; for example, intramuscular ketamine is employed for refractory chronic pain management, and transdermal fentanyl is used in palliative care for breakthrough pain. Special populations require dose adjustments: children often need weight‑based dosing, geriatric patients may have reduced hepatic clearance, and pregnant patients must consider placental transfer.

Adverse Effects and Safety

Side effect profiles are route‑specific. Oral medications frequently cause gastrointestinal upset, while IV infusions can lead to extravasation injury. The following table lists common adverse events with approximate incidence rates.

Route | Common Side Effects | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|---|

Oral | nausea, dyspepsia, diarrhea | 5–20 |

IV | infusion site pain, phlebitis, extravasation | 1–5 |

IM | pain at injection site, hematoma, allergic reaction | 2–10 |

SC | localized erythema, induration, infection | 1–3 |

Transdermal | skin irritation, contact dermatitis, systemic toxicity (e.g., fentanyl overdose) | 1–4 |

Inhalation | irritation, cough, bronchospasm, systemic CNS effects | 3–15 |

Intranasal | nasal irritation, epistaxis, local vasoconstriction | 2–8 |

Black box warnings are most common for drugs with high systemic absorption from transdermal or inhalation routes, such as fentanyl patches (risk of respiratory depression) and high‑dose inhaled corticosteroids (risk of systemic immunosuppression).

Drug interactions depend on the route and the drug’s metabolic pathways. The following table highlights major interactions for IV, oral, and transdermal routes.

Drug | Route | Interaction | Clinical Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

Warfarin | Oral | NSAIDs, antibiotics | Increased INR, bleeding |

Propofol | IV | Cytochrome P450 inhibitors | Prolonged sedation |

Fentanyl patch | Transdermal | Opioid antagonists (naloxone) | Rapid withdrawal, respiratory depression |

Albuterol | Inhalation | Beta‑blockers | Reduced bronchodilator effect |

Monitoring parameters include serum drug levels for narrow‑therapeutic‑index agents, liver function tests for hepatically cleared drugs, and renal function for renally excreted medications. Contraindications vary: for example, transdermal nicotine is contraindicated in severe skin disease; intramuscular epinephrine is contraindicated in patients with certain cardiac arrhythmias.

Clinical Pearls for Practice

Always verify the site and depth of IV access to prevent extravasation, especially in pediatric patients with small veins.

Use the “Rule of 3” for transdermal patches: apply a new patch every 3 days to avoid skin irritation.

When prescribing inhaled corticosteroids, counsel patients on rinsing the mouth to reduce oral candidiasis risk.

For rectal suppositories, ensure the patient is in a supine position for at least 10 minutes to maximize absorption.

Apply a 3‑minute “dry‑dry” technique for intramuscular injections to reduce local pain and improve absorption.

Remember that intranasal drugs bypass first‑pass metabolism; thus, dosing can be up to 50% lower than oral equivalents.

Use the mnemonic “SALT”: SC, IM, IV, and Transdermal routes require different monitoring (Skin, Absorption, Lymphatic, Tissue).

Comparison Table

Drug Name | Mechanism | Key Indication | Notable Side Effect | Clinical Pearl |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Albuterol | β2‑adrenergic agonist | Acute asthma attack | Tachycardia, tremor | Use spacer device to improve delivery. |

Fentanyl patch | μ‑opioid agonist | Chronic cancer pain | Respiratory depression, skin irritation | Check patch integrity weekly to avoid overdose. |

Insulin glargine | Insulin analog | Type 1/2 diabetes | Hypoglycemia, lipodystrophy | Rotate injection sites to prevent lipohypertrophy. |

Desmopressin (intranasal) | Vasopressin analog | Central diabetes insipidus | Hyponatremia, nasal irritation | Administer with a full glass of water. |

Procaine (IV) | Local anesthetic | Local anesthesia for minor procedures | Allergic reaction, methemoglobinemia | Use in patients with G6PD deficiency cautiously. |

Exam‑Focused Review

Students often encounter questions that test their understanding of route‑specific pharmacokinetics and safety. Below are common question stems and key differentiators.

Which route is preferred for rapid reversal of opioid overdose? Answer: Intranasal naloxone or IV naloxone; intranasal offers quick onset with minimal invasiveness.

Which medication should be avoided in a patient with severe hepatic impairment when administered orally? Answer: Drugs with extensive first‑pass metabolism, e.g., diazepam; consider IV or alternate agents.

What is the most common adverse effect of transdermal fentanyl? Answer: Respiratory depression due to systemic absorption.

Which route provides the highest bioavailability for a drug with significant first‑pass metabolism? Answer: Intravenous.

Why is the intramuscular route less preferred for patients with compromised immunity? Answer: Higher risk of local infection at the injection site.

Key facts for NAPLEX/USMLE:

Bioavailability: Oral < 100%, IV = 100%, IM/SC 70–95%.

First‑pass effect: Oral > IV > Transdermal > Inhalation.

Drug–drug interactions are most critical for oral agents metabolized by CYP450 enzymes.

Monitoring: Serum drug levels for narrow‑therapeutic‑index drugs (e.g., digoxin, warfarin).

Patient education: Emphasize adherence, site rotation, and signs of systemic toxicity.

Key Takeaways

Routes of administration determine drug absorption kinetics, bioavailability, and therapeutic onset.

First‑pass metabolism limits oral bioavailability; IV bypasses this entirely.

Transdermal patches offer steady drug delivery but require skin assessment.

Inhalation and intranasal routes provide rapid systemic exposure with minimal first‑pass effects.

Drug interactions are route‑dependent; oral agents are most susceptible to CYP450 interactions.

Special populations (pediatrics, geriatrics, hepatic/renal impairment) require dose adjustments based on PK/PD differences.

Monitoring parameters vary by route: blood pressure for IV, skin integrity for transdermal, and serum levels for narrow‑therapeutic‑index drugs.

Patient education on site selection, rotation, and signs of toxicity improves safety and adherence.

Remember: The route of administration is not a mere delivery method—it is a therapeutic decision that shapes efficacy, safety, and patient quality of life. Tailor your choice to the pharmacological profile, clinical context, and patient preferences for optimal outcomes.

⚕️ Medical Disclaimer

This information is provided for educational purposes only and should not be used as a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of information found on RxHero.

Last reviewed: 2/15/2026

On this page

Table of contents

- Introduction and Background

- Mechanism of Action

- Oral Administration

- Intravenous (IV) Administration

- Intramuscular (IM) and Subcutaneous (SC) Administration

- Transdermal (TD) Administration

- Inhalation (Pulmonary) Administration

- Intranasal (IN) Administration

- Rectal and Vaginal Administration

- Clinical Pharmacology

- Therapeutic Applications

- Adverse Effects and Safety

- Clinical Pearls for Practice

- Comparison Table

- Exam‑Focused Review

- Key Takeaways